my first few days on the ice . . . Story 4

As I mentioned before, I was a little intimidated when I got off the plane at McMurdo.  First, there was the ice fog that filled the plane when the tail ramp was dropped. Then there was the weird, alien zombie-looking guys standing in the snow, staring at us as we came down the ladder. Then there was the total darkness in the middle of the afternoon. Putting all that together, I was beginning to think that maybe, just maybe, I wasn't cut out to be the great adventurer that I saw myself to be. Lying back in my recliner with a beer in one hand and the TV remote in the other was sounding pretty attractive right about then.

First, there was the ice fog that filled the plane when the tail ramp was dropped. Then there was the weird, alien zombie-looking guys standing in the snow, staring at us as we came down the ladder. Then there was the total darkness in the middle of the afternoon. Putting all that together, I was beginning to think that maybe, just maybe, I wasn't cut out to be the great adventurer that I saw myself to be. Lying back in my recliner with a beer in one hand and the TV remote in the other was sounding pretty attractive right about then.

But, I was pretty sure they wouldn't fly me back to Christchurch, even if I started crying like a little baby. So, I sucked it up, tried not to look too scared, and got off the plane. The guys on the ground just looked at us and didn't say much. There wasn't any big celebration of our arrival, but they weren't kicking our butts, either. I saw that as a positive sign!

These guys had been sitting at the bottom of the world, isolated from the rest of civilization for about a year. Most of them had spent the six months of the summer season somewhere in Antarctica then watched as all of the "summer tourists" flew away, back to the real world. They'd only had their own faces to stare at after that, so ours were the first new faces they'd seen in six months or so. Also, these new faces were bringing fresh fruit and vegetables with them! There hadn't been a mid-winter air drop, as far as I know, for a few years. So, fresh food - "freshies" - was definitely welcome. That was something they hadn't seen for a while. And, even more important than the food, we had their mail. We were the bad they had to take with the good that we brought with us.

This also meant that the winter was almost over for them. In six weeks there would be planes, big C-141's, sitting out there on the ice runway that we would would be creating on the annual ice of McMurdo Sound, waiting to take them out of there. They were more than ready for the winter to be over and get the hell off of the ice. So, on the one hand, they were glad to see us.

But, on the other hand, our arrival meant that those damned tourists were back! They had watched them (not me, this was my first trip!) abandon them and fly back to California. Then for the next six months, the winter-overs were left to their own devices as the "summer support" people, as the tourists are known, seem to forget all about them.

Summer support is the part of the command, Naval Support Force, Antarctica (NSFA), that returns to Port Hueneme, California at the end of the summer season.1 It was a normal command, if you can call deploying to Antarctica normal, with regular tours of duty. Their reason for being is to plan for the next summer's deployment in support of science. Science is the whole reason for going to Antarctica. They're also supposed to support the people that stay for the winter, NSFA, Detachment Alpha. Det Alpha people, for the most part, are temporarily assigned to NSFA to spend the summer and subsequent winter on the ice.

During the winter that I was there, summer support became a four-letter word. It just seemed that the winter got no support at all; all the support went into the planning for the next summer season. It seemd like it took them forever to answer our messages. They were ignoring us so they could focus on preparing for their own triumphant return to McMurdo the following year. At least, that was the perception.

So, here we were. The a--holes were back. Back to invade their town. Back to disrupt their lives. Back to use up all of their water! I found out later that there had been some very nasty personality conflicts during their winter and these guys were, for the most part, a pretty miserable bunch. They had split into several factions and had spent most of the winter isolated in their own little groups.

But, now we were invading their "town" and they didn't like that. They stayed in their own groups because they still didn't like each other, but now they all had a common "enemy." Us. Whenever I walked into the galley, I would see a small group hunched over this table and another group hunched over that table and another one over there at that table. They wouldn't be sitting together. They would always be separated by a table or two and their animosity for each other. But, they all glared at me; and any other tourist that happened to invade their domain.

I had just arrived and had almost fourteen months to go, but most of my fellow winter-overs and I would experience some of those same feelings when OUR town was invaded by the summer tourists a year later. -- WE took care of McMurdo and kept everything running for the last six months, you didn't! It was OUR butts that were freezing, building a new ice pier so the re-supply ships could tie up in the summer, not yours! Did you guys spend three months in total darkness, risking your lives for science? Nooooooooo! You were back in sunny California! It was us, tourist, not you! So, don't mess with us! This is our town!

Yeah, it was kinda like that. Well, maybe not quite that extreme, but it's pretty amazing how possessive you become of a place that you just spent six months of your life at with 88 other guys. It was definitely our town and we didn't appreciate newcomers. But, for now it was their town and I, and about 100 or so other guys, were the newcomers. We were the invaders.

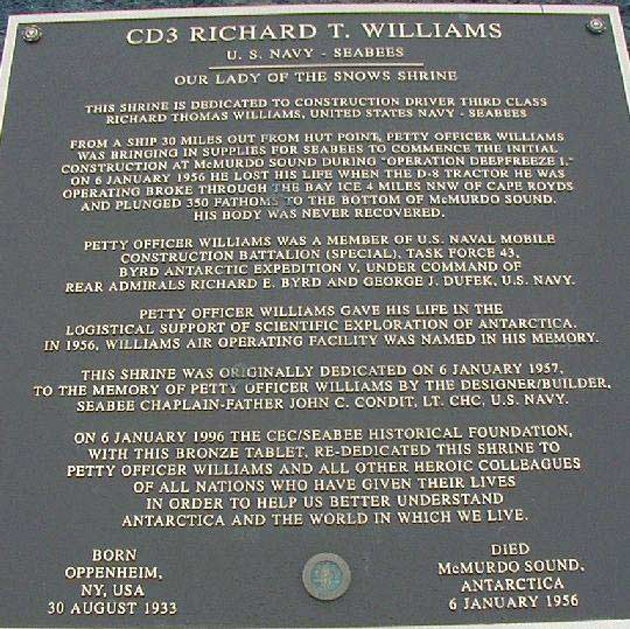

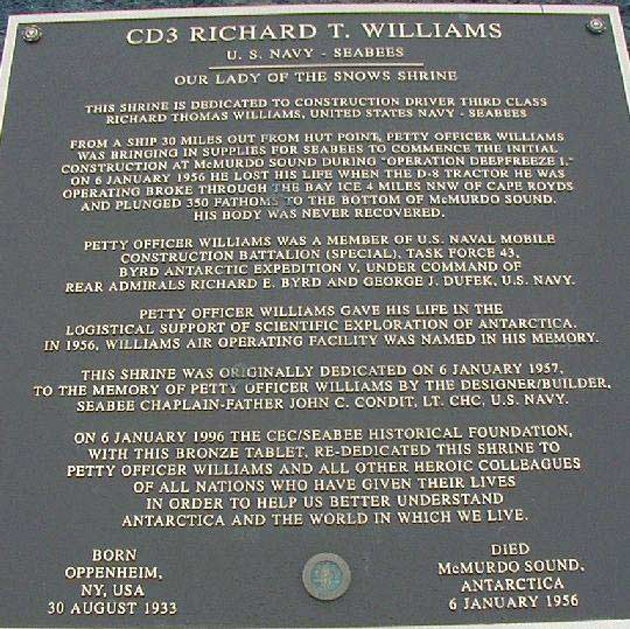

We had landed at the snow-skiway facility known as Williams Field. Williams Field was named after a Seabee Construction Driver third Class (CD3) Richard T. Williams. In 1956, during Deep Freeze I, he had broken through the ice, trapped in the cab of his bulldozer and had perished at the bottom of McMurdo Sound. Rumor had it that Navy divers went down the summer I was there to check on him. He was still inside the cab, preserved in the below-freezing waters of McMurdo Sound. We had heard that his family had requested that he stay there. They considered his bulldozer to be his grave. As far as I know, he's still down there.

Okay, back to the story. After we got off the plane, we were taken to town. Actually, McMurdo Station isn't really a town. It's not even a base. There isn't, or wasn't, a U.S. military presence in Antarctica. Yeah, there were a lot of sailors down there, as well as a few personnel of other services, but we weren't there as military, per se. The Navy had been the first service to explore the Antarctic and had the aviation assets that were required. Plus, sailors were cheap and expendable. The Army, the Air Force and the Coast Guard were also involved in the exploration, in varying degrees and capacities, but the Navy was the only service that would stay in McMurdo through the winter.

When we got into town, we were taken to Hill Cargo. I'm not sure if it was named after somebody named Hill, or if it was because it sits on a little hill. But, that was where we could pick up our baggage before we found our rooms in the barracks. Just like any airline, the world's southern-most airline was prone to losing a passenger's luggage. When the sled arrived with all the bags and was unloaded, one of my bags was missing! Oh, c'mon?!? I carried my own bags to the plane. I may have slept a little on the flight down, but I was pretty sure we hadn't made any stops along the way. There wasn't any place to stop.

They had made that pretty clear when they explained PSR; the "point of safe return." That's a specific point in the flight when you have just enough fuel to make it back to where you started if it's not possible to continue to your destination. Once you pass PSR, you're committed to continue to your destination. So, at PSR, the decision has to be made to turn around or keep going. You still have enough fuel to make it to your destination, but the problem for us was being able to land. At PSR, the weather may be fine, but the weather changes so quickly that landing can become a problem. Our "ace in the hole" was the fact that we wearing skis. Well, not us, the passengers, but the C-130 we were flying in was equipped with skis. If we keep our wheels up, above the skis, we can land away from the bad weather, anywhere there is snow. (And boy, is there a lot of snow down there! 85 percent of the earth's fresh water is contained in the ice and snow that covers the continent of Antarctica) Then, the airfield uses their radar to haul us in as if we were wiggling on the end of a fishing line, like the catch of the day. The risk of what they call a 'white out landing' is that you don't know how far below you the snow is. The plane just slowly descends until the skis meet the snow. That's called a landing. Another danger is that you don't know the condition of the landing surface. It could have obstructions or crevasses. In that case, it's called a crash! However, I have to admit that our landing at McMurdo was the smoothest landing I've ever experienced. I didn't even know we were on the 'ground' until the pilot reversed the propellers to slow down.

Okay, back to the lost-luggage situation. Apparently, my bag was lost somewhere between Williams Field and Hill Cargo. I was told not to worry, though, that they would find it and I would be notified when it had made it into town.

So, I grabbed the bags that had made it in from the aircraft and went to find my room in the barracks. The room assignments had been made by those summer tourists before I ever left California. I had been picked to share a room with two other guys that would be down six weeks later. So, for now, I had a room to myself. As barracks go, it wasn't bad. I had been in a whole lot worse than this. The bathroom and the showers were down the hall. But, it did have a nice "refrigerator." I'll talk more about the showers and the refrigerator in a minute. As I'm emptying my bags and stowing things in my locker, I'm told that my bag had been found and was waiting for me at Hill Cargo. It had fallen off the sled and was found lying in the snow.

I knew that Hill Cargo was less than a hundred yards away from the barracks. I decided that I didn't have to put my "waffle weaves" (long underwear) or the huge, bulky outer pants on just to trot over and pick up my bag. However, I think I did put on my "bunny boots."  Bunny boots were double-insulated thermal boots that were made to keep your feet warm. They were big and bulky and not easy to walk in, but your toes were toasty, and I guess that's the important thing. So, it's out the door, a brisk walk to Hill Cargo, grab my bag and scurry back. Well, that's what it would have been if I'd gone out the right door. But, I couldn't have picked a door farther away from my destination if I had tried. So, I had to walk half way around the barracks before I could even SEE Hill Cargo. Keep in mind that it's at least forty-eight degrees below zero, now with a brisk breeze. Without my long-johns on, all that was between my legs and the cool breeze were thin, cotton Seabee-green pants. I was convinced that by the time I got back to my room that all of the hair on my legs was going to freeze solid, break off and be lying in the top of my boots. IT WAS COLD!!! I decided right then and there that dressing for the weather was probably a good idea. I was not going to make that mistake again. I would make other mistakes, but once was enough for that one.

Bunny boots were double-insulated thermal boots that were made to keep your feet warm. They were big and bulky and not easy to walk in, but your toes were toasty, and I guess that's the important thing. So, it's out the door, a brisk walk to Hill Cargo, grab my bag and scurry back. Well, that's what it would have been if I'd gone out the right door. But, I couldn't have picked a door farther away from my destination if I had tried. So, I had to walk half way around the barracks before I could even SEE Hill Cargo. Keep in mind that it's at least forty-eight degrees below zero, now with a brisk breeze. Without my long-johns on, all that was between my legs and the cool breeze were thin, cotton Seabee-green pants. I was convinced that by the time I got back to my room that all of the hair on my legs was going to freeze solid, break off and be lying in the top of my boots. IT WAS COLD!!! I decided right then and there that dressing for the weather was probably a good idea. I was not going to make that mistake again. I would make other mistakes, but once was enough for that one.

The bag that I picked up was a small bag with mostly "toiletry" articles. When I got it, everything in it was frozen. SOLID! I had to wait for my toothpaste to thaw before I could brush my teeth!

I mentioned the shower and the "refrigerator" a minute ago. We were told that we could only take one shower a week. SAY WHAT?!?! And that shower would be taken between 6pm Friday and 8pm Sunday. Now granted, working up a sweat when it's forty or fifty below zero takes a lot of effort. And it's not quite so bad when everyone is under the same restriction. (I found out later that not everyone was. Hmmmmm.) So, we were all a little smelly. After a couple of weeks, it wasn't that big of a deal. But, it sounded terrible at the time. Three or four weeks later, we were allowed to take not one, but TWO showers a week. It would stay that way through the summer. I found out that the civilians had no water restrictions at all and they could do laundry and shower as often as they wanted to. And because of that, the military had to conserve water. That kinda sucked.

Now, about the refrigerator. My room was on the second floor with a window that gave me a breathtaking view of our small hospital facility; a small, squatty building with a red cross painted on the door. Right outside the hospital was a tiny hut that Dune stayed in. Who is Dune, you ask? Dune was the sled dog, the Huskie, that Scott Base, the New Zealand facility that was a couple of miles away, had loaned the winter-overs at McMurdo to serve as their "mascot." I have absolutely no idea what that was all about, but there he was. I remember looking out the window the first day and seeing Dune down there in the snow, sphynx-like, his back to the wind. He had a nice little shelter there, but apparently he preferred the cold, the snow and the wind. He was in his element.

Okay, back to the refrigerator. The window was good, double-paned, polar-grade Plexiglass. It had wooden shutters on the inside. They were there as an added amount of insulation, but more importantly, to keep the light out during the months of constant sunshine. There were four or five inches between the shutters and the window. This space made an excellent chill box with enough room for a few beers or a bottle of wine. A few minutes inside the shutters and a beer would be ice-cold and ready for consumption. Take it out, replace it with another one, and by the time you finished the first one, the one inside the "refrigerator" was ready. If you were a slow drinker, you drank frozen beer. Later, during the summer when it was warmer, you could slow down a little. But, early in the season, you had to drink fast. It wasn't my idea, but that's just the way it was. It was the code of the South. The deep, deep, deep, DEEP South!

Well, that's all for now. Thanks for stopping by.

Ken

1By 1999, the Navy had been relieved of all duties concerning Antarctic research.

First, there was the ice fog that filled the plane when the tail ramp was dropped. Then there was the weird, alien zombie-looking guys standing in the snow, staring at us as we came down the ladder. Then there was the total darkness in the middle of the afternoon. Putting all that together, I was beginning to think that maybe, just maybe, I wasn't cut out to be the great adventurer that I saw myself to be. Lying back in my recliner with a beer in one hand and the TV remote in the other was sounding pretty attractive right about then.

First, there was the ice fog that filled the plane when the tail ramp was dropped. Then there was the weird, alien zombie-looking guys standing in the snow, staring at us as we came down the ladder. Then there was the total darkness in the middle of the afternoon. Putting all that together, I was beginning to think that maybe, just maybe, I wasn't cut out to be the great adventurer that I saw myself to be. Lying back in my recliner with a beer in one hand and the TV remote in the other was sounding pretty attractive right about then.

Bunny boots were double-insulated thermal boots that were made to keep your feet warm. They were big and bulky and not easy to walk in, but your toes were toasty, and I guess that's the important thing. So, it's out the door, a brisk walk to Hill Cargo, grab my bag and scurry back. Well, that's what it would have been if I'd gone out the right door. But, I couldn't have picked a door farther away from my destination if I had tried. So, I had to walk half way around the barracks before I could even SEE Hill Cargo. Keep in mind that it's at least forty-eight degrees below zero, now with a brisk breeze. Without my long-johns on, all that was between my legs and the cool breeze were thin, cotton Seabee-green pants. I was convinced that by the time I got back to my room that all of the hair on my legs was going to freeze solid, break off and be lying in the top of my boots. IT WAS COLD!!! I decided right then and there that dressing for the weather was probably a good idea. I was not going to make that mistake again. I would make other mistakes, but once was enough for that one.

Bunny boots were double-insulated thermal boots that were made to keep your feet warm. They were big and bulky and not easy to walk in, but your toes were toasty, and I guess that's the important thing. So, it's out the door, a brisk walk to Hill Cargo, grab my bag and scurry back. Well, that's what it would have been if I'd gone out the right door. But, I couldn't have picked a door farther away from my destination if I had tried. So, I had to walk half way around the barracks before I could even SEE Hill Cargo. Keep in mind that it's at least forty-eight degrees below zero, now with a brisk breeze. Without my long-johns on, all that was between my legs and the cool breeze were thin, cotton Seabee-green pants. I was convinced that by the time I got back to my room that all of the hair on my legs was going to freeze solid, break off and be lying in the top of my boots. IT WAS COLD!!! I decided right then and there that dressing for the weather was probably a good idea. I was not going to make that mistake again. I would make other mistakes, but once was enough for that one.